-

Ikigai – A Reason for Being

In the second week of January 2026, I received an email from the charity I had been volunteering for over the last two years, saying they had changed the volunteer shift days and that I was no longer required to attend if the day was inconvenient. I had previously mentioned…

-

A Second Chance to Run

The Night Everything Changed On one night towards the end of March 2021, I jumped out of bed in the middle of the night. My heart was pounding, as if I had just finished a 400-metre time trial. My breath was short and shallow. I choked and coughed. Is…

-

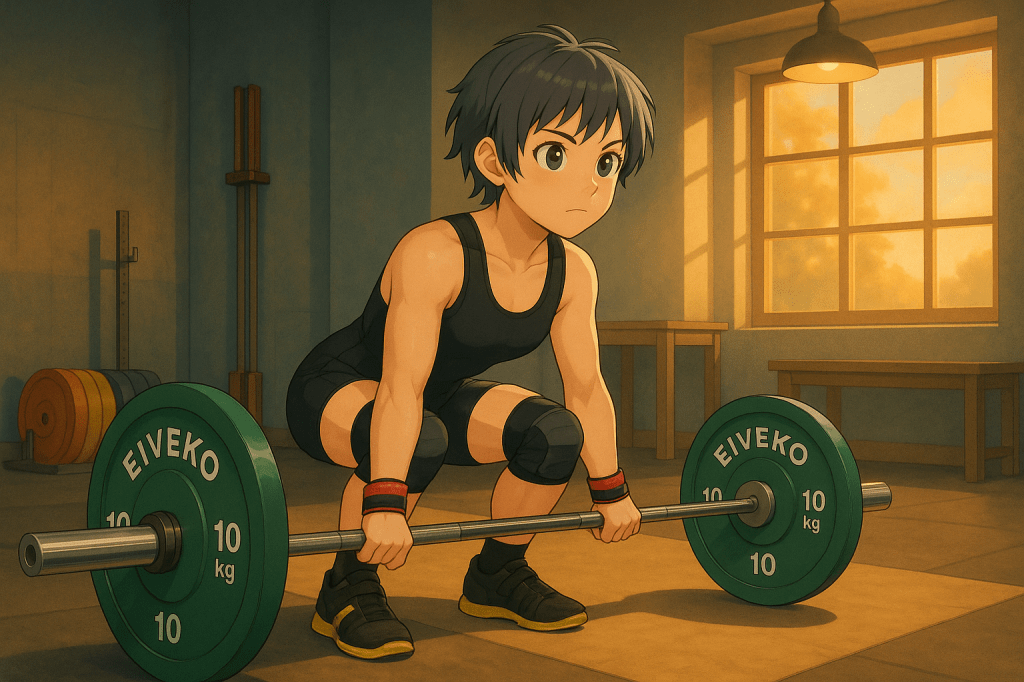

The Body Image in Sports

Weigh-In Pains In the morning of the competition, I enter the weigh-in room. I see the scale on the floor. The technical officials are sitting at the desk. Shoes, trousers, hoodie, and T-shirt. Off they come. I dread this moment as I step onto the scale. I stay still as…

-

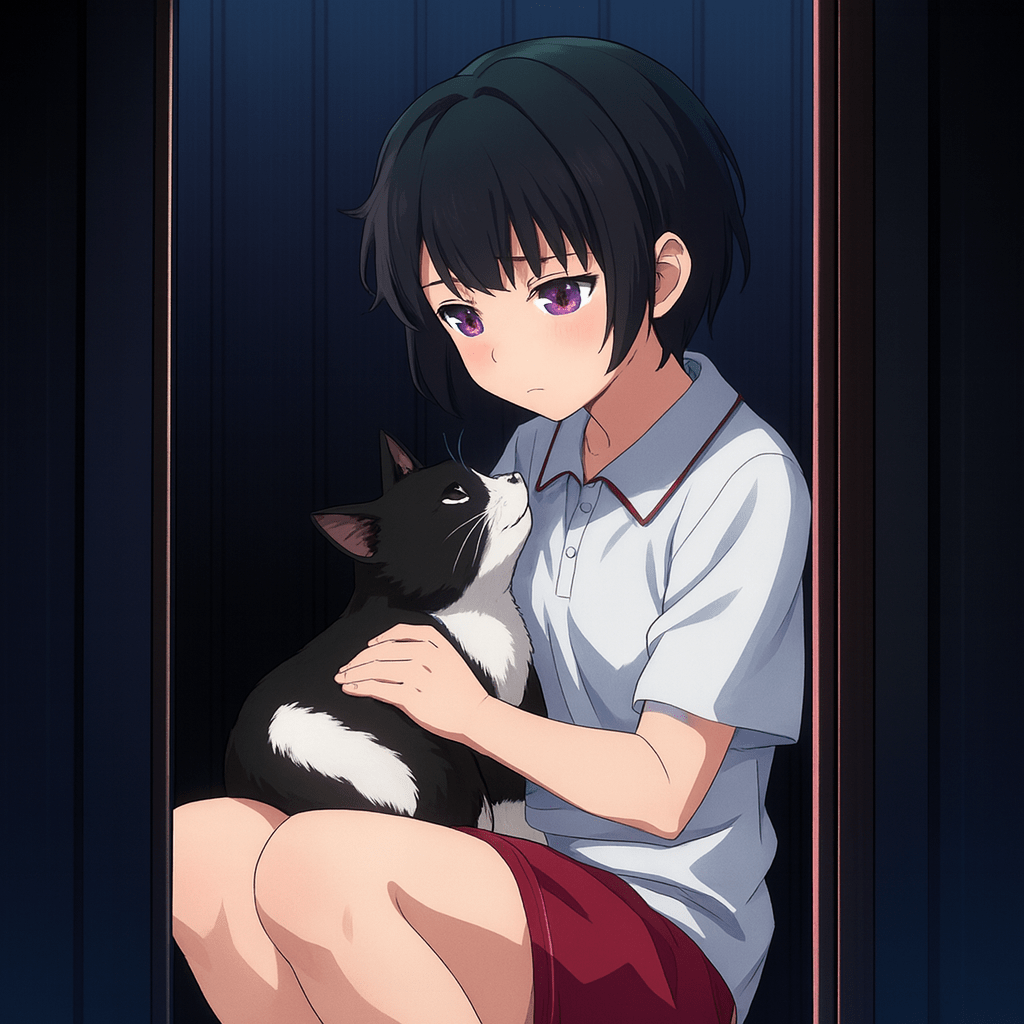

Waking Up to Myself: A Journey from Dreams to Healing

The Dream I was a fly. I was flying, circling above the dinner table, unnoticed and silent. I could go anywhere. Then I noticed a cloud of mist following me. Insect Killer! I frantically flew to the next room, and the kitchen, and I darted in between the cupboard…

-

Breaking Barriers and Finding Strength

Goodbye from HSBC In November 2018, I was made redundant from HSBC. Eight years of hard work. Long hours. A job I didn’t even like. I stood on the platform at Canary Wharf, holding a neat little divorce paper from HR. Shellshocked. I was at a loss. How dare you?…

-

Chasing the Dragon: Five Days Across a Country

In 2017, I stood at the start line of the Dragon’s Back Race — a five-day, 315 km ultra across the rugged spine of Wales. I was 50, not fast, not skilled in mountain navigation, and had no idea if I’d make it past day one. But I showed up.…

-

Two Sports, Two Selves

The training hall was filled with the clank of plates being loaded and unloaded. I sat alone on the floor, preparing my warm-up. Around me, other lifters started moving in. They are followed by their coaches, teammates, and friends, etc. They were there to help the lifters time the lifts,…

-

Learn to Fly – From Trail to 190 Miles

The Northern Traverse wasn’t just a race — it was a crossing. A crossing of landscapes, from rugged coasts to wind-swept moors. A crossing of time, of days stitched together by movement. Most of all, it was a crossing of something inside me — the version of myself who set…

-

The Starting Line

From tears at the start line to leading trail runs, this is a story about running, resilience, and finding your place—one mile at a time.

-

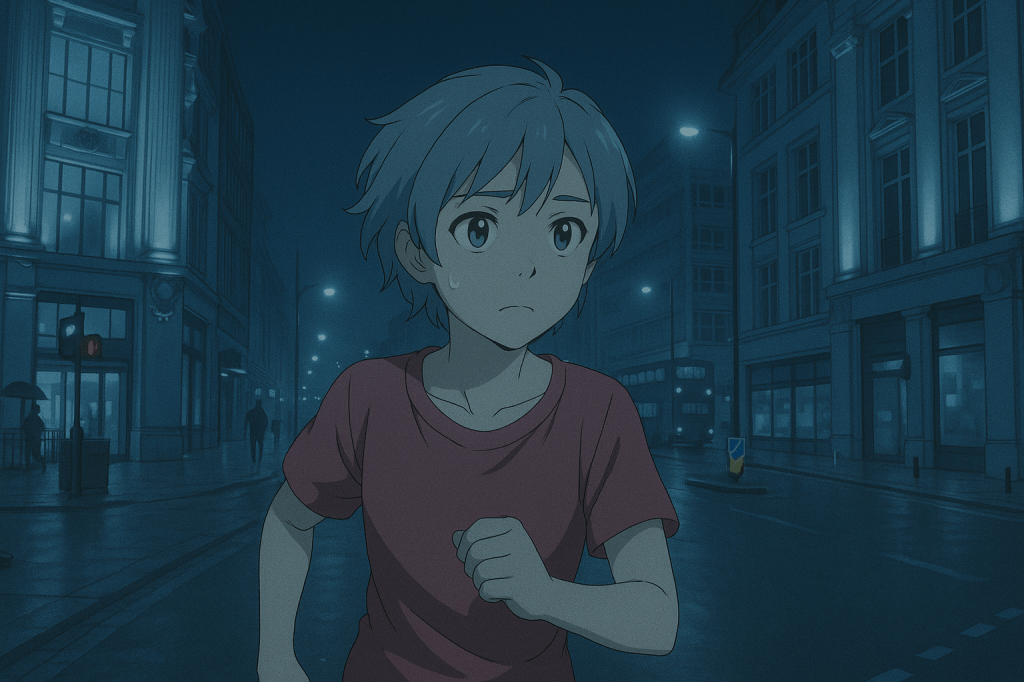

Run, Hisayo, Run!

It was a cold December day in 2003. I was working a night shift at the Crisis Open Christmas shelter in London. I had just finished my MBA but couldn’t find a job. I had one year left on my visa, and I was scared. I didn’t know what would…

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.